Oral Assessment Rubric

What it is:

An oral assessment method to evaluate students' understanding of coding module.

What we did:

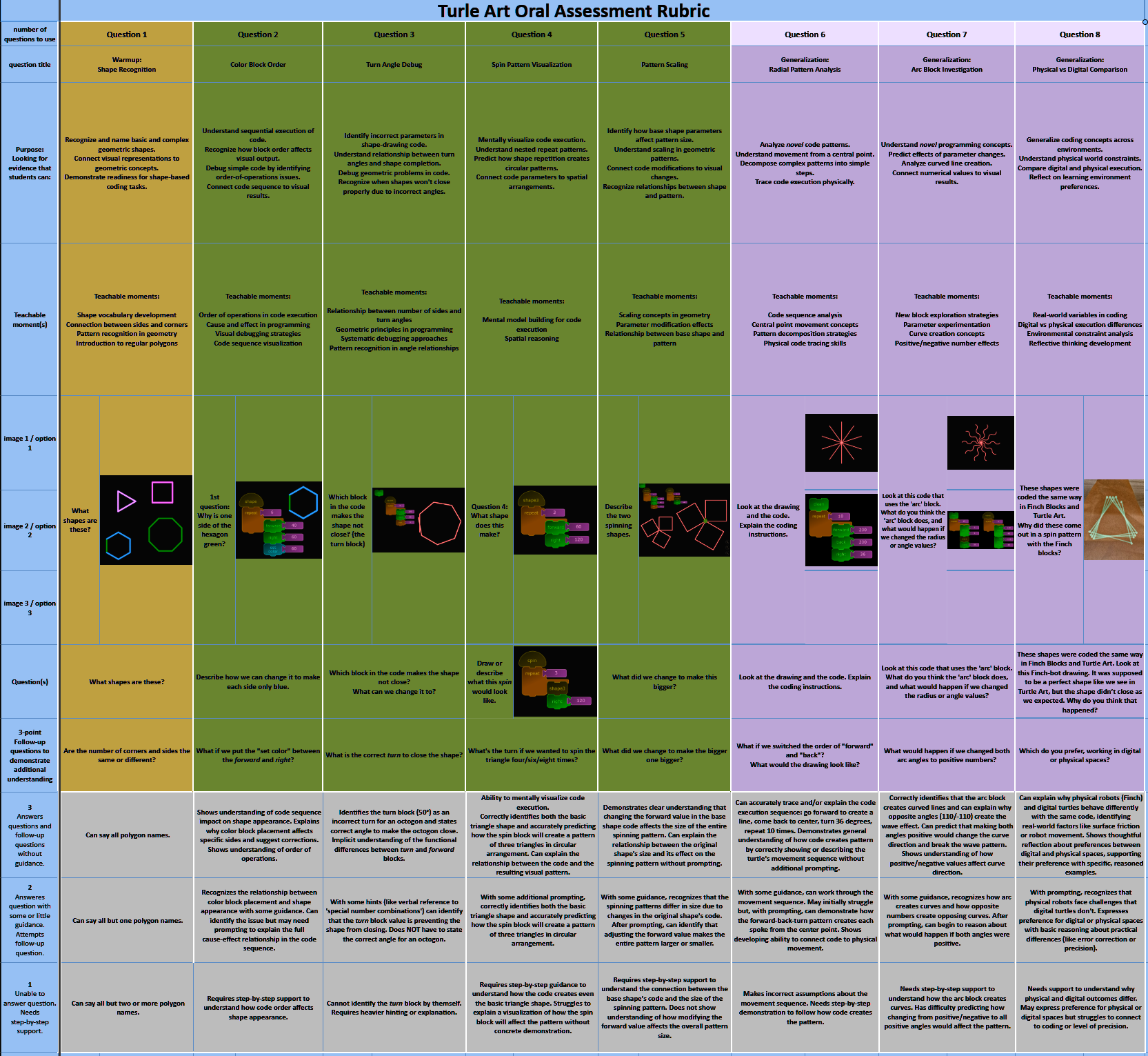

- Design an oral assessment and rubric for Grade 3 Turtle Art.

- Conduct one-on-one assessments.

- Observe how students articulate their understanding of coding concepts.

- In-the-moment teaching.

- Analyze student performance with R.

- Plan curriculum improvements using Understanding by Design (UBD).

Read Full Project Details...

This is our rubric and OA doc (shared viewable)

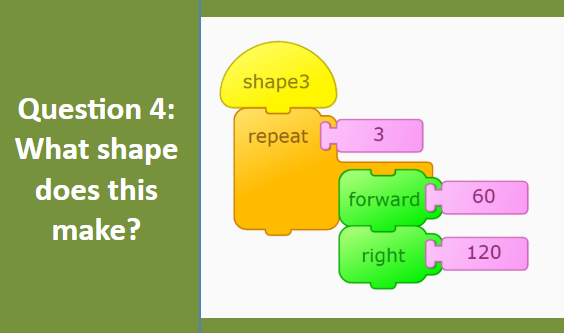

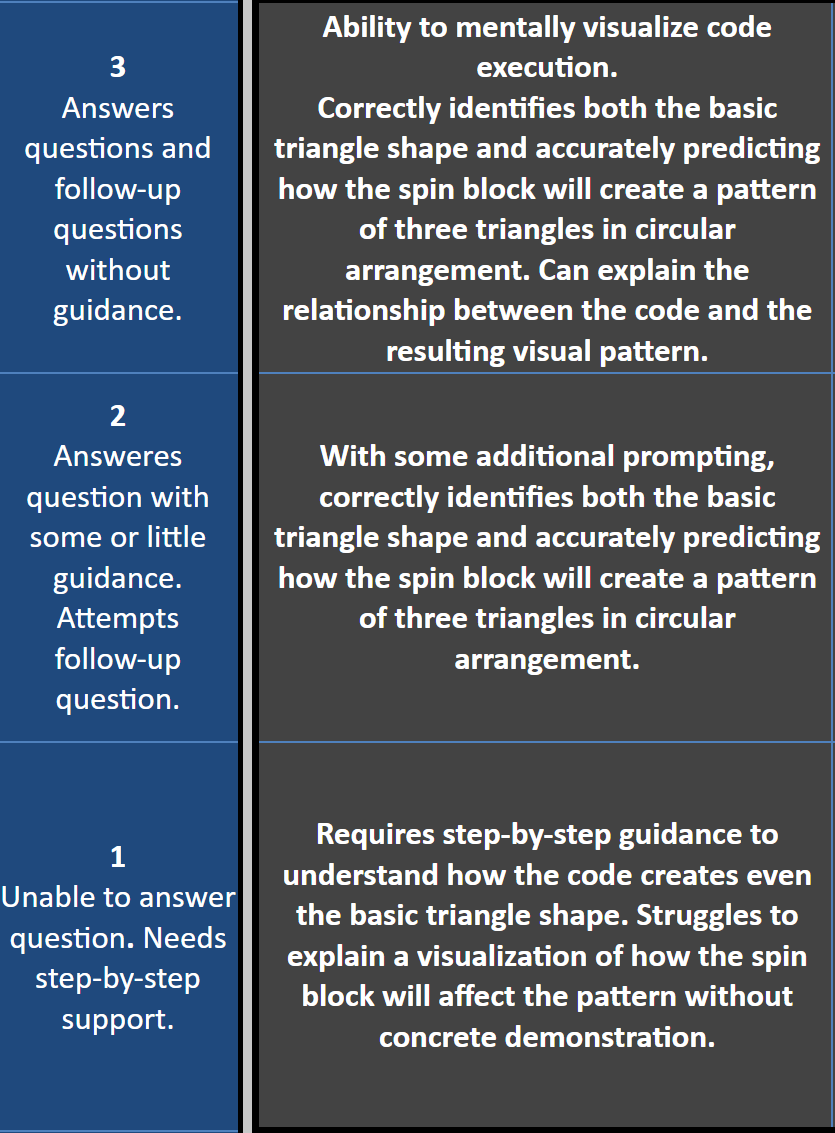

My cooperating teacher and I ended our Grade 3 Turtle Art module with an oral assessment (OA). I designed a rubric to evaluate student responses for this assessment. Using OA, we uncovered how students understand coding concepts by letting them communicate through their thinking.

Application

Speaking interactively can make abstract coding concepts tangible for students. Abstract ideas like code sequencing or pattern logic become more concrete when students must find words or body language to explain and defend their reasoning. They then make the information their own.

Why Oral Assessment Works

Gordon Joughin states that oral assessments measure true student understanding, not just surface recall (Joughin, 2010).

The interactive part of many oral assessments lets educators probe a student’s knowledge, prompting them to articulate their thought processes (Joughin, 1998).

Preparing for and participating in an oral defense often improves student learning, as students expect to explain and justify their ideas (Joughin, 2010).

Oral assessments help confirm academic integrity, as students demonstrate knowledge directly (Joughin, 2010).

They create “moments of articulation” where students connect with and express their knowledge powerfully, making learning tangible and personal (Joughin, 2010). This matches our observation of students “embodying” coding concepts.

Results

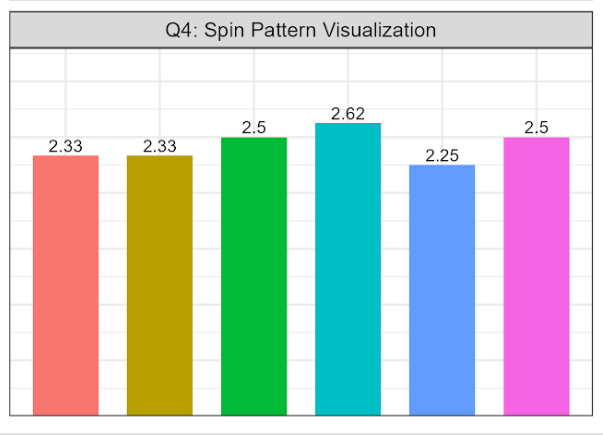

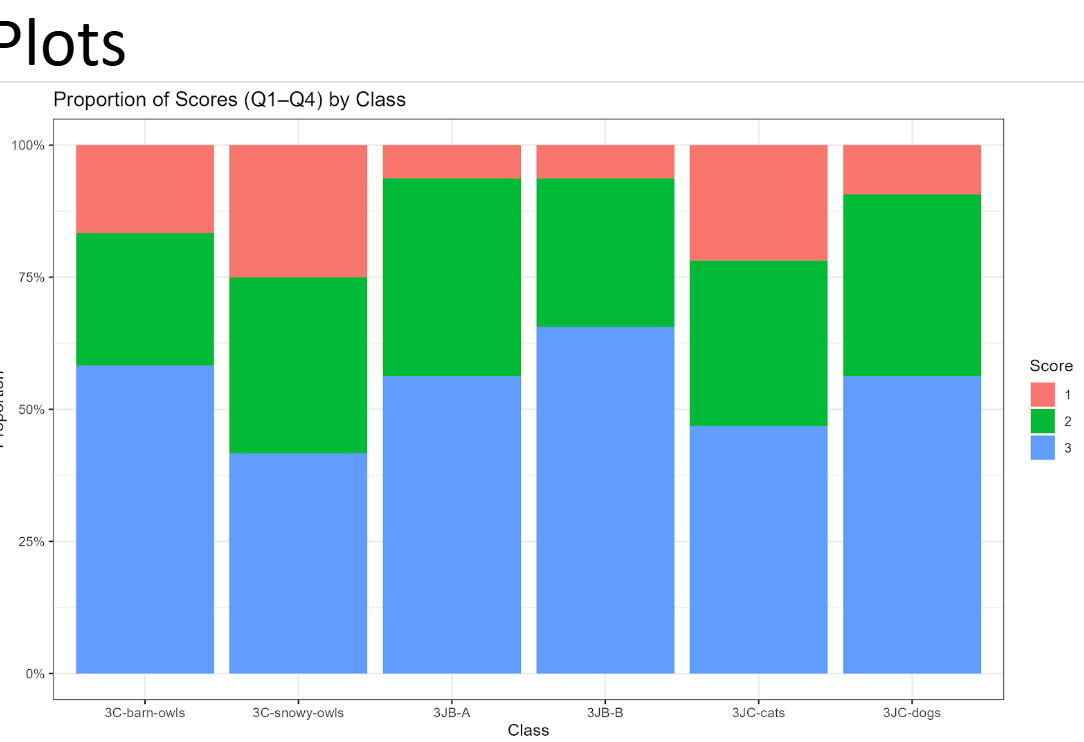

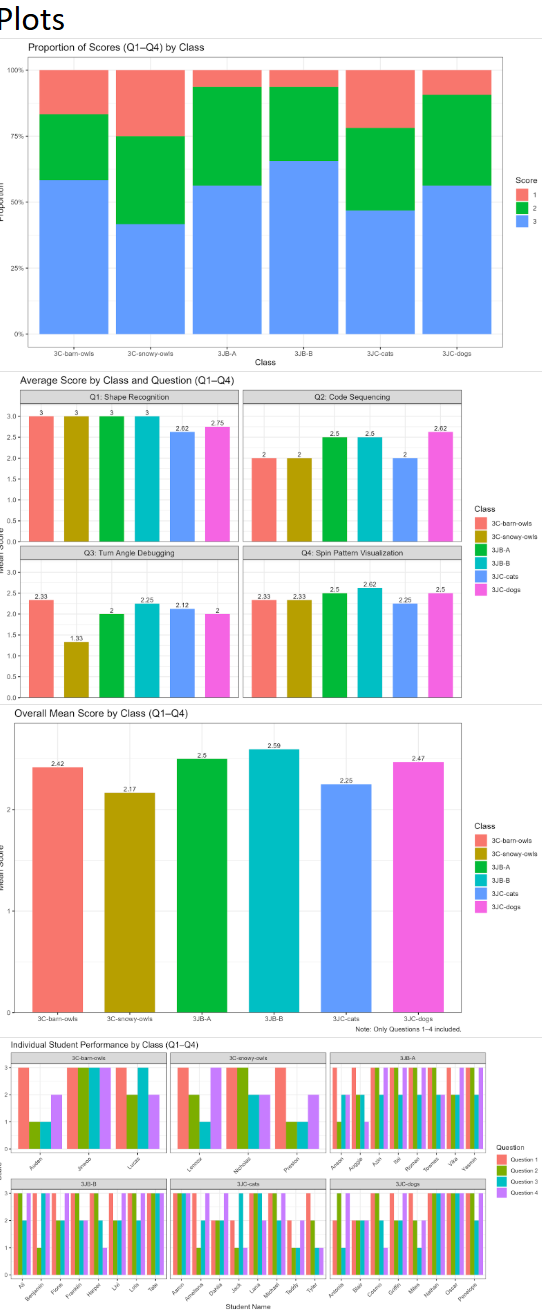

We used the assessment for teaching and we had many teaching/learning moments. For example, while most students correctly identified basic shapes, debugging turn angles proved the most challenging concept for many. Data also showed no large performance difference between classes, but more variance among students within each class. This indicates a need to adapt our teaching to better reach certain students in every class, rather than an issue specific to one class’s instruction.

This experience also helped us define potential enduring understandings and essential questions to guide next year’s module.

Taking Action

Given our results, we plan to refine the Turtle Art module using the Understanding by Design (UBD) framework. This involves defining clear enduring understandings and essential questions upfront to guide all lessons. For example, an enduring understanding might be that “Small code adjustments significantly alter a pattern’s shape and size.” An essential question could be “How do repeated steps and turn angles create specific shapes?”

References

Joughin, G. (1998). Dimensions of Oral Assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 23(4), 367-378.

Joughin, G. (2010). A short guide to oral assessment. Leeds Metropolitan University & University of Wollongong.