(essay) On Anthropomoprhization

Introduction

“We named it ChatGPT and not a person’s name very intentionally” said Sam Altman, founder of Open AI, in October 2023. We are often advised to avoid assigning human traits and characteristics to animals or other entities, a concept known as anthropomorphism. Such caution is based on the idea of human exceptionalism, which suggests that humans are fundamentally different and superior to other beings (de Waal, 2016). This notion of human superiority, as described by de Waal, is influenced by religious beliefs and is prevalent in many scientific fields. However, de Waal argues that “this premise is out of line with modern evolutionary biology and neuroscience” (2016). Nevertheless, humans seem to naturally anthropomorphize even the most basic computer systems (see “The Eliza Effect”, Hall, 2023). To some commentators, this instinct could have unintended consequences, as ascribing human qualities to technology makes it easier for its creators to shirk responsibility for its errors and impacts (Rosenberg, 2023). Other skeptics agree, seeing AI as “just a tool”, and that thinking of AI as an independent, intelligent entity is both misleading and dangerous, as it might cause us to mismanage the technology (Lanier, 2023). These are important philosophical debates that seem certain to intensify and persist. Nevertheless, I make a practical argument for treating AIs like humans, withholding judgment and comment on human exceptionalism and any potential dangers of anthropomorphism, void also of any comment on the humanity, consciousness, or rights of AI systems. We should treat AI systems like humans because research suggests that this is a successful approach.

Human beings and computer systems

Humanness has been built into some of our computer systems for decades, although objectives of these systems vary by discipline. Cognitive architectures like ACT-R and SOAR, introduced in the 1970s and 1980s, model human cognitive processes, primarily for research purposes (Langley, 2009). They abstractly simulate human sensory experiences, such as visual and auditory perception, and interact with their environment to help us advance our understanding of human cognition. Builders of AI systems also deliberately design systems inspired by human cognition, but not necessarily to further our understanding of human cognition, but rather to build more efficient systems. Many recent papers in AI have drawn inspiration from the study of human cognition (Kaizer 2023; Kojima 2023; Lightman 2023; Li 2023; Yao 2023; Zelikman 2022).

By virtue of modality, some AI systems are inherently human-like in terms of their inputs. Like cognitive architectures, latest-generation multimodal AI models like GPT4 are capable of vision and hearing (OpenAI, 2023), while PaLM-E and Gemini have additional capabilities for interacting with the physical environment; (Driess, 2023; Pichai, 2023). Examining the training data that powers these modalities reveals a deep influence of human perspective. This human-centricity is particularly apparent when considering how large language models represent spatial data, constructing a world model through a human lens.

Building a world model

Language models function as token-prediction machines (Shanahan, 2023), generating responses based on their training data. With exceptions, training data is usually human-generated, resulting in agents with human biases.

These biases include a bias for human perception, as opposed to the perception of other biological agents. Professor Margaret Wilson explains in her writing on embodied cognition that “spatial concepts, such as front, back, up, and down… are articulated in terms of our body’s position in, and movement through, space” (2015). The shape of human bodies influence how we perceive the world (Wilson, 2015). Thus, large language models trained on human data share with humans a human-centric understanding of the world. The AI may not be embodied, but its training data is of a human-bodied perspective, which stands upright, with two forward-facing eyes, a nose, and a mouth. As a proof of concept, pure-text LLMs are able to perform spatial-cognitive tasks using only the text-based symbolic data they are trained on from the internet, much like how humans can spatially understand environments through verbal descriptions alone (Sternberg, 2011; Taylor, 1992).

So, language models are token-prediction machines trained on human data. What, then, does it mean to predict the next token well? Cognitive scientist and professor Murray Shanahan says, “Predicting the next token well means you understand the underlying reality that led to the creation of that token” (Shanahan, 2023). That LLMs can answer spatial-cognitive questions well, along with research showing that understanding of physical spaces through a single channel is possible (Taylor, 1992), indicate that LLMs understand the underlying reality of our environment. This understanding extends beyond spatialization, as Open AI chief scientist Ilya Sutskever states, “The way to think about it is that when we train a large neural network to accurately predict the next word in lots of different texts from the internet, what we are doing is learning a world model.”

Treat me like a human

Academic researchers, observing the human-centric world model hardcoded into language models, have applied concepts from human cognition to these models for significant performance gains in research experiments and standard benchmarks. Repeated evidence suggests a strong link between the success of these studies and the practice of treating these systems as akin to human cognitive agents. The following are published examples of applying understanding of human cognition to large language models.

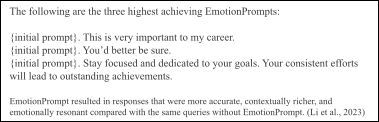

Emotional Stimuli

According to Li et al. in their 2023 paper on emotion and AI, “understanding and responding to emotional cues gives humans distinct advantages in problem-solving.” With this understanding of human cognition, the researchers aimed to give that same advantage to large language models. The authors introduce “EmotionPrompt”, a simple prompting method that enhances outputs in LLMs, including ChatGPT, GPT4, and Llama 2 (Li et al., 2023). Li et al. present a headline figure of 10.9% average improvement in terms of performance, truthfulness, and responsibility metrics when prompting with EmotionPrompt compared to without. On drafting the text of each EmotionPrompts, the authors state: “…we take inspiration from three types of well-established psychological phenomena: Self-monitoring, social cognitive theory, and cognitive emotion regulation” (Li et al. 2023).

As to why EmotionPrompts work, the authors speculate that emotion could be forcing the model either process or simulate processing more deeply and respond in a way that acknowledges those emotional aspects (Li et al., 2023). More concretely, the authors observed that that the emotional stimuli “enriched the original prompts’ representation.” This enrichment is based on the concept that emotional cues add additional context and depth to the prompts, allowing the language model to generate responses that are more nuanced, empathetic, or aligned with human-like emotional responses (Li et al.)

Research continues into how neural networks function (Blazek, 2022) and why emotional stimuli would enhance LLM performance. Nevertheless, the authors applied current understanding of human cognition and emotion to significantly improve language model performance.

Process reasoning

Educators and students understand the importance of showing work when solving problems. This practice demonstrates the student’s thought process to the teacher, while aiding in the student’s cognitive development by encouraging methodical, step-by-step reasoning. Australian mathematicians Norman Wildberger and Daniel Mansfield document an early instance of step-by-step reasoning in their analysis of 3000–4000-year-old Babylonian clay tablets. Amongst the tablets are some of the earliest evidence of formal education (worked math problems) and a table of reciprocals (a reference document, similar to a multiplication table today), which represents the world’s oldest known trigonometric table – huge contributions to our understanding of Babylonian culture and sexagesimal trigonometry (Mansfield, 2017). By studying ancient cuneiform tablets, Wildberger and Mansfield show that ancient Babylonian scribes “thought in algorithms, or procedures, that you go step-by-step to get an answer. That’s how they encoded their information” (Wildberger, 2017). In analysis of multiple instructional and educational clay tablets, they determine it was the procedure that was important to ancient scribes and students, and not the answer, stating that “The answer is usually something very trivial for them in fact, they procedure is what they are being trained on” (Wildberger).

These same principles of multi-step reasoning can be used to gain similar benefits in output quality in large language models. Lightman et al., motivated by reducing costs and increasing efficiency of training LLMs, researched whether models solve mathematical problems better with outcome supervision, which provides feedback (or reward) for a final result, or process supervision, which provides feedback for each intermediate reasoning step (Lightman et al., 2023). In other words, do the models perform better when simply delivering the answer, or when they show step-by-step reasoning? Lightman et al. found that process supervision (working problems step-by-step) led to a 2.6x improvement in training data efficiency when compared to outcome (final answer only) supervision. Process supervision also helped in reducing false positives – cases where a model produced the correct answer but with incorrect reasoning or logic.

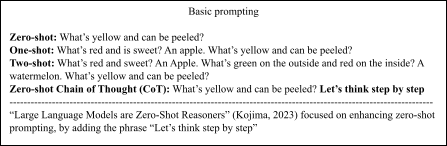

Other researchers similarly have similarly applied step-by-step reasoning to language models. In their 2023 paper, titled “Large Language Models are Zero-Shot Reasoners”, Kojima and colleagues created a new prompting method to improve zero-shot performance in LLMs called “Zero-shot-Chain of Thought”. “Chain of thought” indicates the process of breaking down a problem into smaller, more manageable steps. “Zero-shot” means the user offers no examples when making a query, while “one-shot” means providing one example, “two shot” means providing two examples, and so on. Zero-shot responses typically have lower accuracy due to the lack of contextual examples. Kojima et al. found that incorporating the phrase “Let’s think step by step” to zero-shot prompts significantly enhances LLMs’ reasoning capabilities and output responses.

To use or not to use Zero-Shot-CoT is like the choice between meticulously solving a math problem on paper, detailing each step, versus mentally calculating it. The more complex the problem, the more advantageous it becomes to use chain of thought reasoning, as it helps to methodically work through each step and reduce errors that might occur from attempting to solve everything at once. Zero-shot-CoT is based on our same understanding of the benefits of multi-step reasoning used by Babylonian scribes with ancient math, and Lightman et al. to train models with ‘process supervision’ rather than ‘outcome supervision’. Using Zero-shot CoT, Kojima et al. saw significant improvement on two math tasks: accuracy improvement on the GSM8K math dataset increased by 30.3%, and a notable 61% increase in scores on the MultiArith datasets (2023).

Iterative Reasoning

Humans can improve reasoning skills by taking longer to reach conclusions and considering more alternative conclusions (Sternberg, 2006). Taking longer allows the reasoner to review past information, which then informs subsequent decisions in an iterative process. The concept of iterative reasoning, where one systematically evaluates multiple possibilities before arriving at a conclusion, is both a human trait and an applicable strategy in enhancing language models. Yao et al. (2023) in their ‘Tree of Thoughts’ (ToT) paper, use and cite cognitive science research on decision making to significantly improve problem-solving capabilities in LLMs.

In the language of Daniel Kahneman’s “System 1 and System 2” theory of human cognitive processing (2011), language models operate in system 1 – a fast, automatic, intuition-based mode of thinking (Yao et al., 2023). Imagine for a moment that you are limited to responding to a query like our current language models: Once you begin you can’t backtrack. If your response begins poorly, it’s difficult to recover. You can’t plan beyond the next token. To know when your response is complete, you must look behind. This imagination exercise offers a glimpse as to why models are poor at planning (and sometimes poor at answering generally) – “Please write a story in 100 words” rarely results in a story of exactly 100 words.

Operating in system 1 does not allow for planning. To steer an LLM’s thinking toward a slower, more deliberate, and more logical “system 2”-type reasoning ToT guides a language model through a series of steps, or reasoned paths, with different branches and backtracking to guide an AI toward a response that is more coherent, logically consistent, and reflective of a deeper understanding of the query.

To illustrate how Tree of Thoughts (ToT) works let’s look at the research paper’s creative writing experiment. The ToT-equipped chatbot functions as follows: The chatbot is prompted to perform a creative writing task. Where a normal chatbot would generate one final output and deliver it to the user, the ToT-equipped chatbot begins with writing five ‘plans’ for the assignment. It then evaluates each of the five plans, noting each plan’s strengths, weaknesses, and areas of potential. It ‘votes’ on the best plan and uses that plan as a foundation to complete the writing assignment. This approach generates considerable text output when compared to standard querying, and requires extra time, computing power, and that the system have a large context window (running memory of the conversation).

The above experimental workflow features one “ToT step”: several outputs are made, voted on, and then acted upon. Other experiments in the paper involve multiple ToT steps, along with backtracking, that allow the AI to revisit previous branches if the chosen branch isn’t as fruitful as expected. By simulating system 2 reasoning in this way, we instruct the AI first to show us what it’s thinking, and only then give us the answer (Kaizer, 2023).

Yao et al. drew inspiration from cognitive scientist Allen Newall and his colleagues in designing ToT: “To design such a planning process, we return to the origins of artificial intelligence (and cognitive science), drawing inspiration from the planning processes explored by Newell, Shaw, and Simon starting in the 1950s. Newell and colleagues characterized problem solving as search through a combinatorial problem space, represented as a tree. We thus propose the Tree of Thoughts (ToT) framework for general problem solving with language models.” This structure allows a ToT-equipped AI to decide which branch to take with heuristics, explore different continuations within a thought process, plan, look ahead, and backtrack (Yao et al), mimicking human cognition in both design and function.

In this early experiment in the application of tree of thought reasoning to large language models, ToT significantly improved problem-solving abilities in three tasks difficult for current LLMs: creative writing (higher coherence score by AI and human scoring), Game of 24 (74% success rate compared to 4% without ToT), and 5x5 Crosswords (20% game win success rate vs. 0%). The Tree of Thought paper, which built off Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning by Kojima et al., has immediate implications for today’s large language models. AI researcher Lukasz Kaizer thinks CoT and ToT reasoning strategies will play a crucial role in the development toward artificial general intelligence (AGI) in the coming months and years (Kaizer, 2023). By introducing system 2 thinking to LLMs with tree of thought reasoning, Yao et al. draw on concepts from human cognition in an aim to liberate LLMs from their “token-level, left-to-right decision-making processes,” to construct a more human-like approach to problem solving.

Concluding Remarks

These examples of artificial intelligence research show the process of iterative improvement to AI systems, informed by concepts of human cognition. Each iteration results in an AI system more human-like than the last, opening opportunities for the application of additional human cognitive knowledge, and enhancing the rationale for treating these systems as human.

To most effectively use human-centric AI systems, we should think of and interact with them as if they are humans. By acknowledging the results of these studies and others, everyone, from AI scientists, to software developers, to consumer-level chatbot users, can leverage our understanding of humans and apply it to interactions with language models for better experiences.

The implications of this conclusion emphasize key philosophical and ethical questions about artificial intelligence in society. Regardless how these debates unfold in the future, thinking of and treating AIs like humans delivers positive results today. In fact, you are not likely to get far as an AI researcher if you don’t. And as a chatbot user, you would be wise to include such statements as “Let’s think step by step” and “This is very important to my career” to your prompts so as to not be comparatively disadvantaged.

Abstract

Research in artificial intelligence consistently shows that applying knowledge of human cognition to AI systems enhances their performance. This is an iterative process – as we further embed aspects of human cognition into AI systems, they become more human, opening avenues for more applications. For this reason, I propose that the best way to interact with and think of AI systems is as if they are human beings. I begin by analyzing the human-like characteristics already embedded in language models to better understand why they respond to human cognitive approaches. I then examine aspects of human cognition – emotional engagement, step-by-step reasoning, and iterative decision-making processes – and the direct application of these concepts in large language models (LLMs), as well as the positive results. These studies serve as empirical evidence supporting human treatment of AI systems.

Final Paper – MSTU-4133: Computers and Cognition

Posted on December 20, 2023

For the Best Experience, Treat Me Like a Human!

| Yuri Gushiken | mkg2145@tc.columbia.edu |

Teachers College, Columbia University

MSTU-4133: Cognition and Computers

Dr. Rachel Um

20 December 2023

References

| Altman, S., & Murati, M. (2023, October 21). OpenAI CEO Sam Altman and CTO Mira Murati on the Future of AI and ChatGPT | WSJ Tech Live 2023 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=byYlC2cagLw |

Awasthi, A., Sarawagi, S., Goyal, R., Ghosh, S., & Piratla, V. (2019). PIE: Parallel Iterative Edit Models for Local Sequence Transduction. GitHub repository. https://github.com/awasthiabhijeet/PIE

Benchetrit, Y., Banville, H. J., & King, J.-R. (2023, October 18). Toward a real-time decoding of images from brain activity. Meta. Retrieved [18 Dec, 2023], from https://ai.meta.com/blog/brain-ai-image-decoding-meg-magnetoencephalography/

Blazek, P. J. (2022, March 2). Why we will never open deep learning’s black box. Towards Data Science. Retrieved from https://towardsdatascience.com/why-we-will-never-open-deep-learnings-black-box-4c27cd335118

Chemero, A. (2023). LLMs differ from human cognition because they are not embodied. Nature Human Behaviour, 7(11), 1828-1829. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01723-5

de Waal, F. (2016, April 8). What I Learned From Tickling Apes. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/10/opinion/sunday/what-i-learned-from-tickling-apes.html

Driess, D., Xia, F., Sajjadi, M. S. M., Lynch, C., Chowdhery, A., Ichter, B., Wahid, A., Tompson, J., Vuong, Q., Yu, T., Huang, W., Chebotar, Y., Sermanet, P., Duckworth, D., Levine, S., Vanhoucke, V., Hausman, K., Toussaint, M., Greff, K., Zeng, A., Mordatch, I., & Florence, P. (2023). PaLM-E: An Embodied Multimodal Language Model. arXiv:2303.03378 [cs.LG]. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.03378

Frith, C. D., & Frith, U. (2012). Mechanisms of Social Cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 287–313. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100449

Germanidis, A. (2023, December 11). Introducing General World Models. Runway Research. https://research.runwayml.com/introducing-general-world-models

Hall, D. (Producer). (2019, December 10). The ELIZA Effect. 99% Invisible. Retrieved from https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/the-eliza-effect/

| Kaizer, L. (2023). (2023, November 2). Deep Learning Decade and GPT-4. AI HOUSE | Lukasz Kaiser, OpenAI | AI for Ukraine: Season 2 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrvc2rPuXTE |

Kojima, T., Gu, S. S., Reid, M., Matsuo, Y., & Iwasawa, Y. (2023). Large Language Models are Zero-Shot Reasoners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.11916. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2205.11916

Javaheripi, M., & Bubeck, S. (2023, December 12). Phi-2: The surprising power of small language models. Microsoft Research Blog. Retrieved from https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/blog/phi-2-the-surprising-power-of-small-language-models/

Jones, A. L. (2021). Scaling Scaling Laws with Board Games. arXiv:2104.03113. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2104.03113

Karpathy, A. [Andrej Karpathy]. (2023, November 22). [1hr Talk] Intro to Large Language Models [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zjkBMFhNj_g

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Langley, P., Laird, J. E., & Rogers, S. (2009). Cognitive architectures: Research issues and challenges. Cognitive Systems Research, 10(2), 141-160.

Lanier, J. (2023, April 20). There Is No A.I. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/science/annals-of-artificial-intelligence/there-is-no-ai

Lightman, H., Kosaraju, V., Burda, Y., Edwards, H., Baker, B., Lee, T., Leike, J., Schulman, J., Sutskever, I., & Cobbe, K. (2023). Let’s Verify Step by Step. arXiv:2305.20050. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2305.20050

Li, C., Wang, J., Zhang, Y., Zhu, K., Hou, W., Lian, J., Luo, F., Yang, Q., & Xie, X. (2023). Large Language Models Understand and Can Be Enhanced by Emotional Stimuli. Institute of Software, CAS; Microsoft; William & Mary; Department of Psychology, Beijing Normal University; HKUST. https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.11760

Mansfield, D. F., & Wildberger, N. J. (2017). Plimpton 322 is Babylonian exact sexagesimal trigonometry. Historia Mathematica, 44(4), 395-419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hm.2017.08.001

Ni, P. (2019, December 8). 3 Reasons People Become Manipulative. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/communication-success/201912/3-reasons-people-become-manipulative

OpenAI. (2023). GPT-4 Technical Report. Retrieved from [https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.08774].

OpenAI. (2023, February 24). Planning for AGI and beyond. OpenAI Blog. Retrieved from https://openai.com/blog/planning-for-agi-and-beyond

Peng, J. (2018, December 4). How human is AI and should AI be granted rights? Columbia Computer Science. Retrieved from https://blogs.cuit.columbia.edu/jp3864/2018/12/04/how-human-is-ai-and-should-ai-be-granted-rights/

Pichai, S., & Hassabis, D. (2023, December 6). Introducing Gemini: our largest and most capable AI model. The Keyword. Google. Retrieved from https://blog.google/technology/ai/google-gemini-ai/?utm_source=gdm&utm_medium=referral#sundar-note

Rosenberg, S. (2023, December 20). AI’s colossal puppet show. Axios. Retrieved from https://www.axios.com/2023/12/20/ai-puppet-show-robots-autonomy

Shanahan, M. (2023). Machine Learning Street Talk (MLST). 2023. #93 Prof. Murray Shanahan - Consciousness, Embodiment, Language Models [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/BqkWpP3uMMU?si=deBaQu4ggoSgbjK0

Sternberg, R. J. (2011). Cognitive psychology (6th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Sternberg, R. J. (2006). The Nature of Creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 18(1), 87–98.

Sutskever, I., & Huang, J. (2023, March). Ilya Sutskever (OpenAI) and Jensen Huang (NVIDIA CEO): AI Today and Vision of the Future [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ckz8XA2hW84

Taylor, H. A., & Tversky, B. (1992). Spatial mental models derived from survey and route descriptions. Journal of Memory and Language, 31, 261-292. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-596X(92)90014-O

Wildberger, N. J. (2017, January 16). Old Babylonian mathematics and Plimpton 322: The remarkable OB sexagesimal system [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J5Ug3Cr8RUE&t=1315s

Wilson, M. (2002). Six views of embodied cognition. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 9(4), 625-636.

Yao, S., Yu, D., Zhao, J., Shafran, I., Griffiths, T. L., Cao, Y., & Narasimhan, K. (2023). Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.10601v2

Zelikman, E., Wu, Y., Mu, J., & Goodman, N. D. (2022). STaR: Bootstrapping Reasoning With Reasoning. arXiv:2203.14465. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2203.14465

[1] In pursuit of more efficient computer systems, AI also contributes to cognitive science. See “Toward a real-time decoding of images from brain activity” by Meta: https://ai.meta.com/blog/brain-ai-image-decoding-meg-magnetoencephalography/

[2] The PHI-2 model, distinct in its use of solely synthetic data for training, offers an alternative approach to traditional human-generated data sets. See https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/blog/phi-2-the-surprising-power-of-small-language-models/

You can download the full paper here: